New Fossil Skeleton: A brand-new discovery out of Kenya is turning the world of human evolution upside down. Scientists have unearthed the most complete Homo habilis fossil skeleton ever found—and guess what? It doesn’t look much like us at all. That’s right: the earliest members of the human genus Homo weren’t the upright, long-legged ancestors we imagined. Instead, they were still climbers, built for gripping branches, not walking city streets. This fossil doesn’t just add a piece to the puzzle—it redraws the edges of the entire picture.

Table of Contents

New Fossil Skeleton

You might be thinking: “Okay, cool bones… but what does this have to do with me?” Everything. This discovery reminds us that being human isn’t about walking upright or having smartphones. It’s about adapting, surviving, and evolving. It’s about the journey, not the finish line. And that journey? It’s still ongoing. As we face global challenges—climate change, migration, technological shifts—it helps to remember that our ancestors were survivors too. They climbed trees. They made tools. They figured it out. So can we. We’re still becoming human.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Fossil Name | KNM‑ER 64061 |

| Species | Homo habilis |

| Estimated Age | 2.03–2.1 million years |

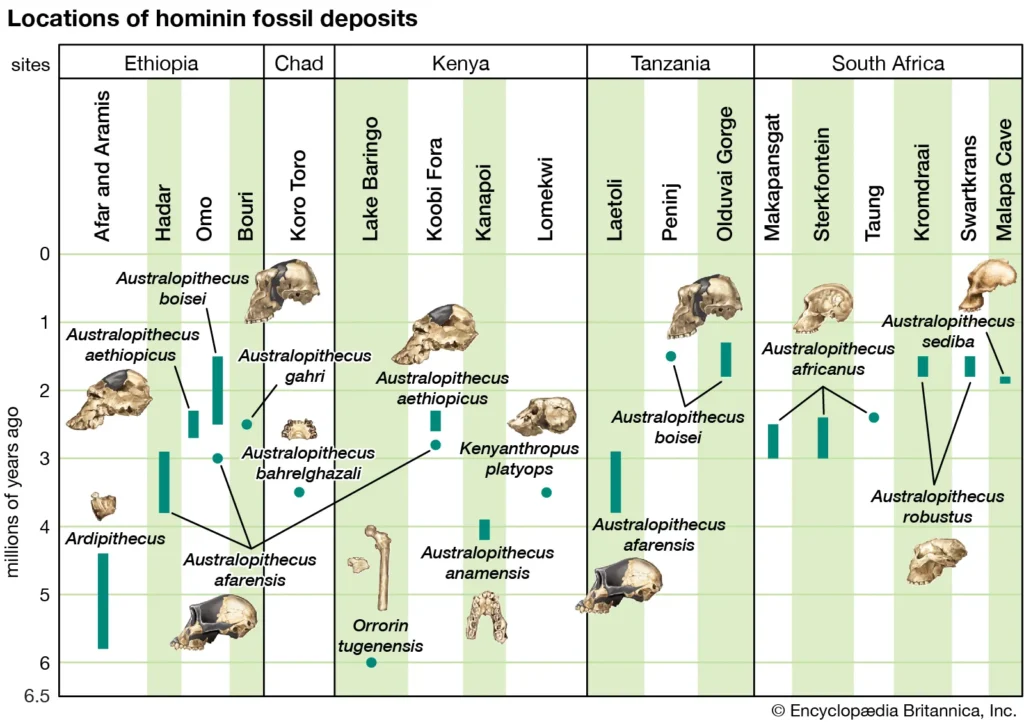

| Found In | Koobi Fora, Lake Turkana, Kenya |

| Discovered By | Kenya National Museums & University of Missouri team |

| Notable Traits | Long arms, curved fingers, short femur, small stature |

| Significance | Reshapes how we view early human evolution |

| Scientific Reference | LiveScience Article |

Who Was Homo habilis and Why Should You Care?

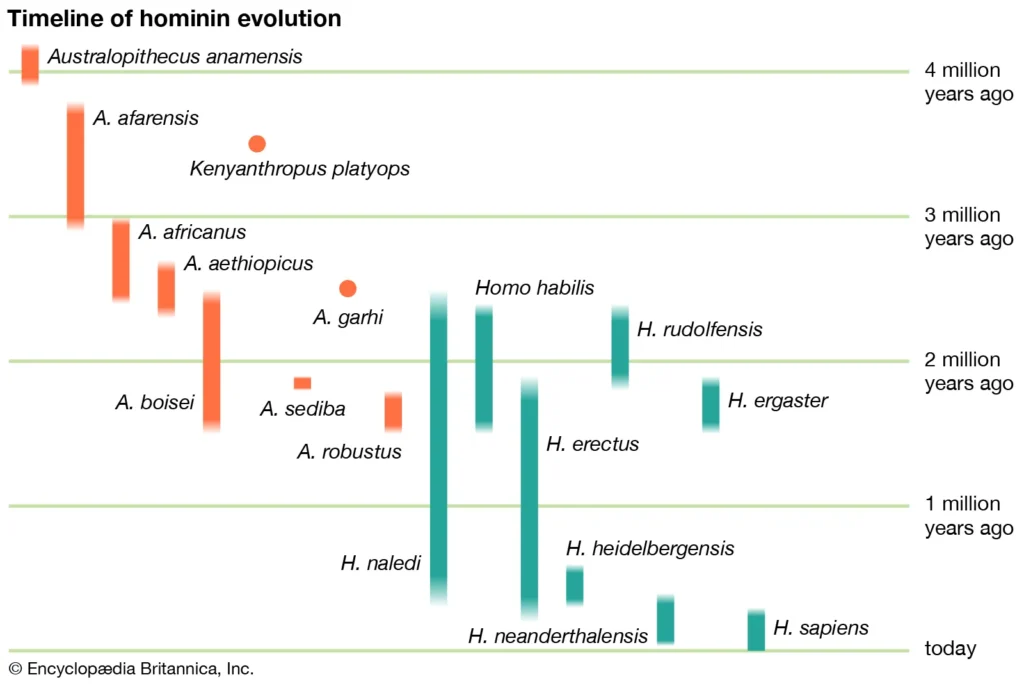

In the human family tree, Homo habilis is one of our earliest known relatives—nicknamed the “handy man” for being one of the first species to use tools. First discovered in the 1960s by famed anthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey, this species represents a bridge between more ape-like ancestors like Australopithecus and more advanced species like Homo erectus.

We’ve long believed that Homo habilis walked upright like us, had begun evolving human-like limbs, and was well on the path toward becoming us. But this newly described fossil found at Koobi Fora in Kenya tells a different story.

The individual behind fossil KNM‑ER 64061 likely stood about 4’3” tall, weighed 70–80 pounds, and still had limbs optimized for climbing, not running. This wasn’t a prototype of Homo sapiens. It was a very different kind of human.

What the New Fossil Skeleton Tells Us About Body Structure?

The fossil includes key elements: a femur (thigh bone), portions of the pelvis, upper limb bones, and vertebrae. Together, they offer the most complete view yet of a Homo habilis skeleton. Here’s what scientists observed:

Limb Proportions

- The arms are disproportionately long, much more like those of Australopithecus than modern humans.

- The femur is short, indicating a short stride—not ideal for long-distance walking.

- Curved finger bones suggest this individual still used their hands for climbing.

This “ape-like” body would’ve made Homo habilis a poor long-distance walker, which was once considered a defining trait of the genus Homo.

“The fossils reveal that Homo habilis had retained many features from its climbing ancestors,” says Dr. Carol Ward, a lead researcher. “They weren’t built like us yet—not even close.”

Revising the Timeline of Human Evolution

This changes the evolutionary story in some major ways.

1. The Human Body Shape Evolved Later Than We Thought

Many scientists assumed our signature body structure—long legs, short arms, upright walking—evolved early in the Homo line. But this fossil shows that Homo habilis still looked and moved more like earlier, primitive hominins.

It wasn’t until Homo erectus, about 1.8 million years ago, that we begin to see the body plan we recognize today.

2. Evolution Happened in a “Mosaic” Fashion

Traits didn’t evolve all at once. Instead of switching from ape to human overnight, our ancestors evolved piece by piece—a big brain here, a new knee joint there. This is called mosaic evolution.

So while Homo habilis may have had the brain for tools, its body was still catching up.

Life of a Tree-Climbing Human: How Did They Live?

Despite their place in the human genus, Homo habilis probably didn’t live like you or me—or even like later cave-dwelling humans.

Shelter & Mobility

They likely slept in trees at night to avoid predators. Their long arms and curved fingers were perfect for climbing and grabbing branches.

Diet & Tools

They were scavengers and gatherers, using Oldowan tools (primitive chipped stones) to scrape meat off bones or crack open nuts.

Social Behavior

Most experts believe they lived in small social groups, sharing resources and protecting each other from danger—behaviors also observed in modern great apes.

Broader Implications for Science and Education

This fossil doesn’t just shift theories. It changes textbooks, teaching models, and museum exhibits. For example:

- Textbooks may need updates showing Homo habilis with more primitive features.

- Museum reconstructions might revise body shapes based on this fossil.

- Curriculums might put more emphasis on mosaic evolution and variability in early Homo species.

It also encourages young scientists and students to dig deeper (pun intended) into paleoanthropology, where new finds continue to surprise the world.

Career Tip: How to Get Into Paleoanthropology

Fascinated by early humans? Here’s how you can explore this field professionally:

Start with Education:

- Bachelor’s in Anthropology, Archaeology, or Biology

- Graduate studies in Paleoanthropology or Human Evolution

Fieldwork Experience:

- Join digs through programs like:

- Koobi Fora Field School

- Leakey Foundation Grants

Read and Stay Informed:

- Journals: Nature, Journal of Human Evolution, Science

- Blogs: SAPIENS, Smithsonian Human Origins

Skills Needed:

- Comparative anatomy

- Fossil analysis

- Evolutionary biology

- Strong storytelling and data interpretation

From Bones to Belief: A Native Perspective

In many Native American cultures, we understand time as circular rather than linear. Everything returns. Everything connects.

The bones of Homo habilis aren’t just fossils—they’re messengers from the ancestors. They remind us that the journey to become human wasn’t a race. It was a dance—through trees, through hardship, through survival.

Some Native communities hold oral traditions about shapeshifters, ancestors that moved between worlds—land and tree, human and animal. These fossils echo those stories. They show that we didn’t come from one straight line, but from many branches reaching for the sun.

Archaeologists Identify the Oldest Poisoned Arrows Ever Found, Dated 60,000 Years

Researchers Decode the Fragrances Used in Ancient Egyptian Mummy Balms

Mummy CT scans Reveal What Daily Life Did to Ancient Egyptian Priests