Scientists studying contaminated water beneath Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant have discovered active microbial communities living inside radiation-exposed reactor structures more than 13 years after the 2011 nuclear disaster. The findings suggest life can persist in environments previously considered sterile and may reshape nuclear cleanup strategies as well as ongoing astrobiology research into life beyond Earth.

Table of Contents

Unexpected Life Discovered Around Fukushima’s Reactor Site

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Discovery | Living bacteria found in submerged reactor infrastructure |

| Environment | High radiation, darkness, chemical contamination |

| Significance | Impacts nuclear cleanup and extraterrestrial life research |

Researchers say Fukushima’s Reactor Site will remain a long-term scientific observatory. Each year of monitoring offers insight into how ecosystems respond to radiation and industrial catastrophe, and may guide both safer nuclear technologies and future planetary exploration missions.

What Researchers Found Inside Fukushima’s Reactor Site

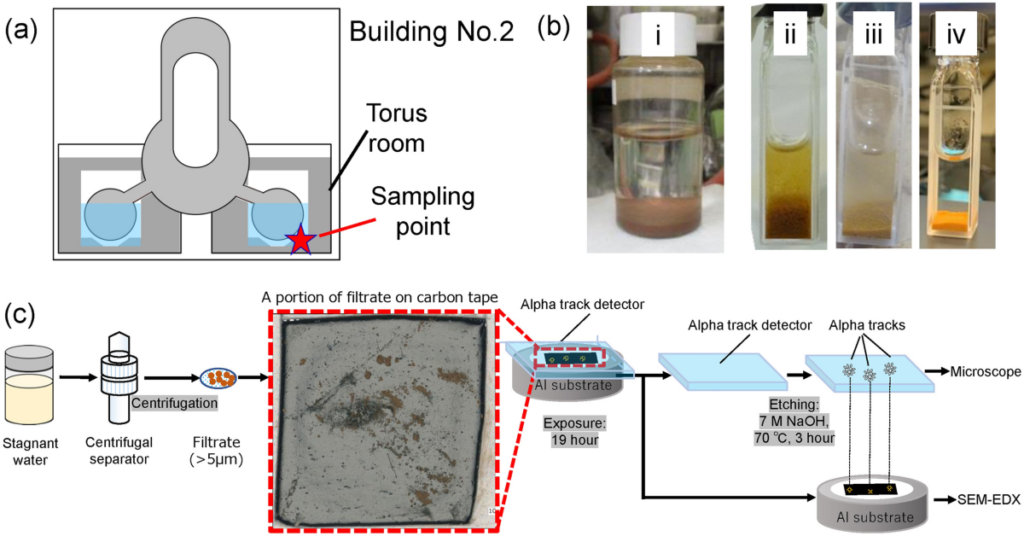

Scientists collected samples from flooded containment areas beneath reactor vessels known as torus rooms. These chambers accumulated cooling water after emergency operations to prevent further overheating following the 2011 meltdowns.

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), experienced catastrophic cooling failure after an earthquake-triggered tsunami disabled electrical systems. Since then, hundreds of tons of water have been used daily to cool nuclear fuel debris, creating an unusual chemical environment.

Researchers analyzing sediment and water samples identified diverse bacterial populations growing on metal piping, structural concrete, and filtration equipment. DNA sequencing confirmed the organisms were metabolically active and reproducing.

The discovery surprised scientists because the environment contains ionizing radiation levels capable of damaging DNA. Many researchers expected sterilization rather than colonization.

Instead, multiple species were present simultaneously, forming a functioning ecosystem rather than isolated organisms.

Environmental microbiologists reported the communities included organisms typically found in aquatic environments. These were not exclusively known radiation-resistant microbes.

How the Microbes Survive Radiation

Biofilms Provide Natural Shielding

The organisms survive by forming dense biological layers called biofilms. These sticky microbial coatings attach to surfaces and trap minerals and organic material.

Biofilms act as physical barriers. The outer layers absorb radiation energy, allowing inner cells to remain viable. The same phenomenon occurs in some hospital infections and underwater pipelines.

Scientists studying radiation-resistant microbes say group survival strategies are often more effective than individual resistance. Collective structures create micro-habitats where radiation exposure is significantly reduced.

Chemical Energy Replaces Sunlight

The microbes do not rely on photosynthesis. Instead, they use chemical reactions involving metals released by corrosion.

They oxidize iron, manganese, and sulfur compounds in contaminated water. This process generates metabolic energy.

The environment at Fukushima’s Reactor Site effectively supplies fuel. Metal pipes, concrete, and dissolved reactor materials create constant chemical gradients. These gradients act as an energy source similar to deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

Protection Through Repair Mechanisms

In addition to shielding, many microbes appear capable of repairing damaged DNA. Radiation breaks genetic strands, but some bacteria possess efficient repair enzymes. Researchers believe repair activity combined with biofilm protection allows survival.

Context: The 2011 Fukushima Disaster

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck northeastern Japan. The resulting tsunami exceeded protective seawalls and flooded emergency generators.

Without power, cooling systems failed in three reactors. Hydrogen explosions followed, releasing radioactive materials into the atmosphere and ocean.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the accident was classified Level 7 — the highest severity rating — matching the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

More than 150,000 residents evacuated surrounding areas. Large exclusion zones remained restricted for years, though some areas have gradually reopened after decontamination.

Today, decommissioning is expected to take 30 to 40 years. Removing melted fuel debris remains one of the most difficult technical tasks in nuclear engineering.

Implications for Nuclear Cleanup

The microbial discovery introduces new variables for engineers managing nuclear cleanup.

Corrosion Risks

Certain bacteria accelerate corrosion. By consuming metals, they weaken structural components and storage systems.

Engineers worry microbial activity could:

- degrade pipes

- damage containment vessels

- alter water filtration systems

Long-term storage tanks holding treated radioactive water may also be affected.

Possible Cleanup Benefits

However, the organisms may also help.

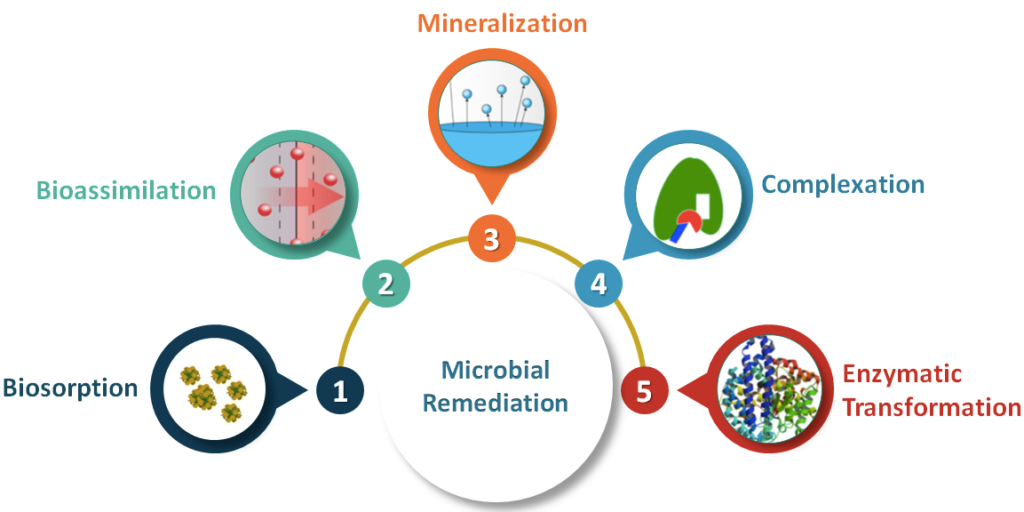

Some bacteria bind heavy metals and radioactive isotopes. Environmental engineers are studying whether microbes could assist decontamination by trapping radioactive particles.

This biological approach is known as bioremediation. It has been used in oil spill cleanup and mining pollution control.

If proven effective, microbes could reduce long-term environmental contamination.

Why Astrobiologists Are Paying Attention

The conditions at Fukushima’s Reactor Site resemble environments beyond Earth:

- no sunlight

- high radiation

- toxic chemistry

- confined water

Researchers studying extremophile life say the findings strengthen the possibility of microbial ecosystems in subsurface environments on Mars or beneath the ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Astrobiologists already suspect that if extraterrestrial life exists, it is most likely microbial and underground. Radiation on planetary surfaces would normally destroy organisms. But protective niches could allow survival.

The Fukushima microbes demonstrate that life may not require stable planetary climates. It only needs localized chemical energy and protection.

Comparison With Chernobyl

Scientists also compare the discovery with post-accident research near Chernobyl in Ukraine.

At Chernobyl, certain fungi appear capable of using radiation as an energy source through melanin pigments. The Fukushima case differs. Here, microbes do not appear to feed on radiation but rather avoid it through shielding and repair.

The comparison shows multiple survival strategies exist in high-radiation environments.

Together, the findings challenge previous assumptions that radiation automatically eliminates ecosystems.

Environmental and Ocean Impact

Since the disaster, treated water has been released gradually into the Pacific Ocean after dilution. Japanese authorities and international inspectors say radiation levels meet safety standards.

Still, the discovery of microbial ecosystems adds a new research dimension. Scientists now examine whether bacteria influence how radioactive isotopes move through groundwater and marine environments.

Marine biologists are also monitoring coastal sediments to see whether similar microbial communities develop outside the plant.

What the Discovery Does Not Mean

Scientists emphasize the discovery does not suggest radiation is safe for humans.

Human tissue lacks the protective mechanisms seen in microbial colonies. Exposure to high ionizing radiation increases cancer risk and damages organs.

The organisms at Fukushima’s Reactor Site are microscopic bacteria, not animals or mutated species.

Public health regulations remain unchanged, and restricted areas remain carefully monitored.

Ongoing Research

Japanese universities, international laboratories, and nuclear agencies continue analyzing samples. Researchers aim to determine how microbial activity affects radioactive element mobility, corrosion, and water purification systems.

Future robotic probes inside reactor buildings may collect deeper samples near melted fuel debris.

Scientists also plan long-term monitoring as radiation levels decline. Observing ecological changes may reveal how ecosystems recover after nuclear disasters.

One environmental microbiologist involved in the research noted that extreme environments may be hostile to humans but not necessarily to life itself.

FAQs About Unexpected Life Discovered Around Fukushima’s Reactor Site

Q: Are the microbes dangerous?

No. They are naturally occurring environmental bacteria. Radiation, not microbes, poses the hazard.

Q: Does life mean the reactor is safe?

No. Radiation exposure levels still require strict safety protocols.

Q: Why is this discovery important?

It informs nuclear engineering, environmental remediation, and the search for extraterrestrial microbial life.

Q: Could this help future nuclear accidents?

Possibly. Understanding microbial corrosion and bioremediation could improve response strategies.