Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers: Why some ant species survive by sheer numbers instead of heavy defense is a lesson straight from nature’s playbook — and it holds deep insights for professionals, scientists, kids, and everyday backyard observers alike. In the wild world of ants, it turns out the ones that survive best aren’t always the ones with the hardest armor. Instead, some ants win by relying on what Americans know best: strength in numbers and hustle. Imagine you’re watching an army of ants move across the forest floor — it looks chaotic, but there’s a pattern. Now zoom in. You’ll notice something: these ants aren’t tanks; they’re light, fast, and most of all, many. Some species don’t bulk up their workers for solo fights. They just build more workers. A lot more. And guess what? That strategy works.

Table of Contents

Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers

Some ant species survive by sheer numbers instead of heavy defense — and that’s not a flaw, it’s a feature. Nature shows us that survival isn’t about being the biggest or strongest. It’s about being adaptable, coordinated, and abundant. For these ants, success means working together, reproducing quickly, and reacting fast as a group. From Silicon Valley startups to Army field operations, the lesson is clear: individual toughness is great, but unity and numbers win wars. These tiny creatures are living proof.

| Topic | Insight / Statistic | High-Authority Source |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Strategy | Some ants invest in numbers instead of individual defense | ScienceDaily – University of Maryland study |

| Colony Size Link | Species with less armor tend to have bigger colonies | Phys.org reporting on Science Advances |

| Cuticle Investment | Ants’ cuticle varies from 6%–35% of body volume | SciTech Daily |

| Global Ant Count | Earth may house ~20 quadrillion ants | Popular Science |

| Social Evolution | Shared labor and cooperation are keys to success | Discover Magazine |

| Scientific Journal | Full research published in Science Advances | science.org |

Understanding the Strategy: Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers, Not Armor

In nature, survival often comes down to trade-offs. Ants have limited resources, and evolution has taught them to spend those wisely. Instead of creating a few tough-as-nails workers that can take on any predator, some ant species make thousands of less-armored, more cooperative individuals.

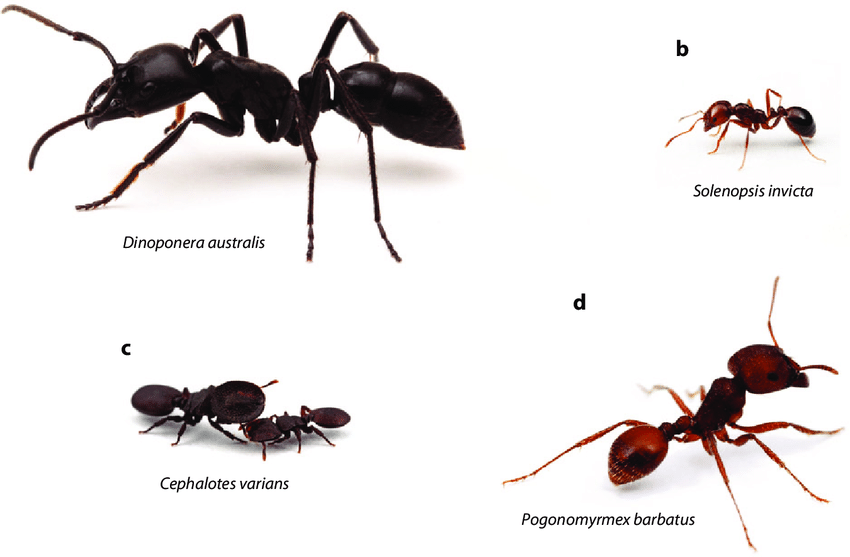

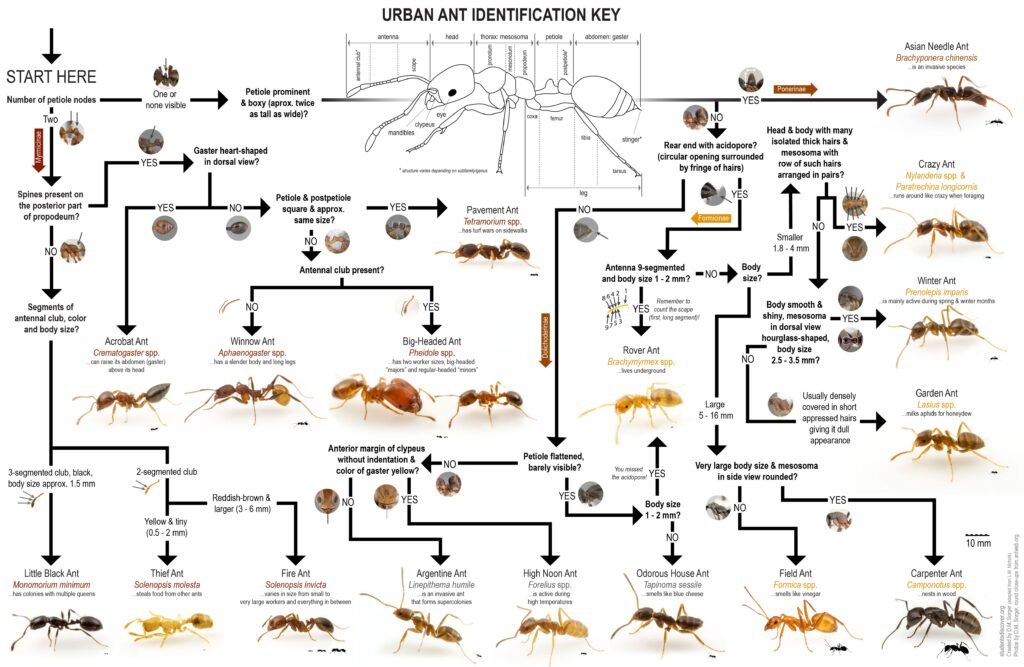

This is backed by a 2025 study from researchers at the University of Maryland and published in Science Advances. The team analyzed over 300 species of ants and discovered a fascinating pattern: species that put less energy into creating strong, heavily armored bodies had way more workers in the colony. It’s a deliberate strategy that favors quantity over quality—and it’s working.

Why Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers Works: The Power of the Colony

1. Cuticle Investment is Costly

Ants’ hard exoskeletons (called cuticles) protect them from threats, but they also require significant nutrients—especially nitrogen, which can be scarce in nature. The study found that some ants devote as little as 6% of their body volume to cuticle, while others reach up to 35%.

The ones with less cuticle? They were much more numerous.

A less-protected worker can still contribute meaningfully—especially if it’s part of a team of 10,000. That’s how colonies with “weaker” ants still manage to dominate ecosystems. It’s not about being the strongest individual. It’s about building the strongest community.

2. Group Defense and Division of Labor

What these ants lack in armor, they make up for in coordinated defense. When under attack, some species release pheromones that signal others to swarm the threat. A single predator can be overwhelmed by a coordinated response from hundreds of ants—even if none of them is particularly strong.

Plus, in large colonies, ants specialize. Some forage, others build tunnels, and others tend to the queen or defend the nest. This division of labor is a major evolutionary advantage and allows them to work with astonishing efficiency.

3. More Workers = More Coverage

Large colonies can:

- Explore larger areas for food

- Outcompete other insect species

- Recover quickly if they lose workers

- Build massive, complex nests underground or in trees

This “many hands make light work” approach isn’t just for ants. It’s how human tribes, communities, and companies have grown too.

Real-World Examples of Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers

Let’s dive into specific species that have embraced this strategy:

Argentine Ants

These tiny brown ants are a global invasive powerhouse. Individually, they’re fragile and no match for predators. But they form supercolonies—some stretching hundreds of miles—and operate like a single mega-organism. One colony in California contains billions of individuals. They’ve pushed out native ants and even overwhelmed small animals.

Their strength? Cooperation and numbers, not individual toughness.

Army Ants

They’re the stuff of legends—masses of fast-moving ants consuming everything in their path. Each worker is light and not particularly tough. But army ants succeed by constantly moving and overwhelming prey through sheer volume. When they hunt, they send tens of thousands of workers forward like a living net.

Leafcutter Ants

Found in the Americas, leafcutter ants build some of the largest insect societies on Earth, with colonies that can exceed 8 million workers. They aren’t individually strong, but their advanced farming behavior (they cultivate fungus) and huge workforce make them major players in forest ecosystems.

This Is Bigger Than Bugs: Lessons for Humans

Here’s where things get deep.

Business and Team Strategy

Ever wonder why big companies with huge workforces often outcompete boutique firms—even when the latter seem more skilled? It’s the ant principle: size and coordination matter. A startup might be lean and tough, but if a massive organization rallies a coordinated effort, they often win in scale.

Military and Defense

Military strategists study swarm tactics and distributed systems—many of which are inspired by ants. In fact, swarm robotics is an emerging field where autonomous drones behave like ant colonies, responding to threats as a group rather than as individuals.

Ecology and Conservation

Understanding how different species survive—whether by strength, speed, or numbers—helps conservationists protect endangered species or manage invasive ones. When ants invade ecosystems by sheer numbers, they can wipe out delicate native species. Knowing their strategy helps us design better countermeasures.

Step-by-Step Breakdown: How Some Ant Species Survive by Sheer Numbers Strategy Works

Step 1: Resource Allocation

Ant colonies decide (through evolution) how to “spend” their limited resources. They can either:

- Invest in thicker armor, stronger jaws, and fewer workers

- Or invest in many, less-protected workers

The latter has proven more successful for species that live in stable environments with fewer threats or that rely heavily on cooperation.

Step 2: Pheromonal Coordination

Ants have sophisticated communication systems using pheromones. This means even a lightly armored ant can call for backup. Some species can mobilize thousands of defenders within seconds using chemical signals.

Step 3: Rapid Reproduction

High-numbers ants reproduce fast. Colonies can bounce back from disasters, move nests quickly, or exploit resources before competitors even arrive.

What the Science Says?

In the 2025 Science Advances study, researchers took detailed 3D scans of ants across 300+ species and calculated how much volume each ant allocated to cuticle versus soft tissue. Then they correlated that with colony size. The results were crystal clear: less armor, more workers.

Interestingly, this strategy appeared more in highly social species, suggesting that as ants evolve more cooperative behavior, they shift toward a “quantity-first” survival strategy. It’s the same principle that governs human cities, bee hives, and even coral reefs.

Scientists Study a Spider Whose Web Can Stretch Across an Entire River

Mammoth Cave Fossils Reveal Life From 325 Million Years Ago

How Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter Without Hibernating