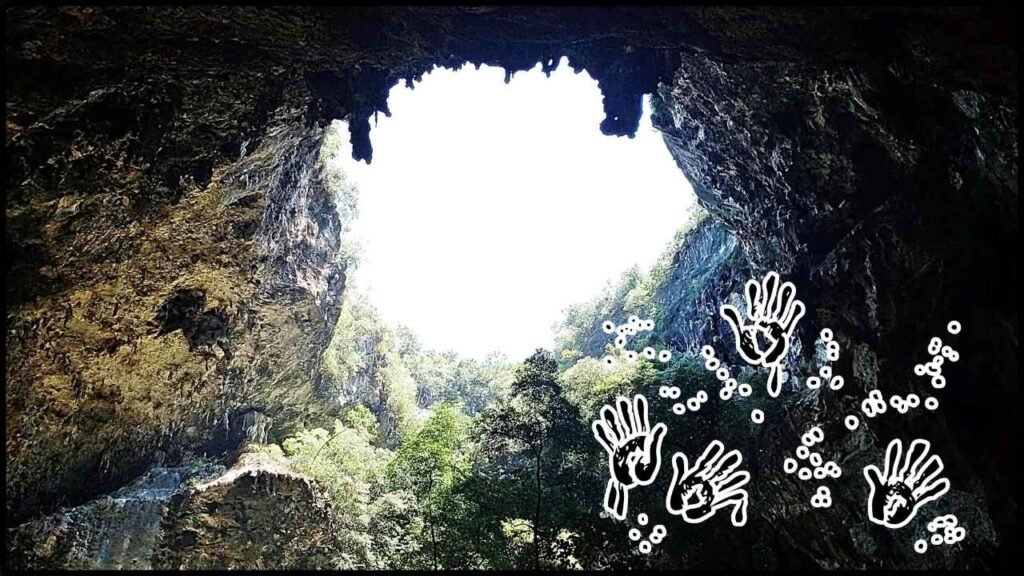

7,800-Year-Old Cave Handprint: long before smartphones, cities, or even written language, someone just like you placed their hand on a rock wall, blew pigment around it, and walked away. Now, 67,800 years later, scientists have found it—and it may be the oldest human artwork ever discovered. That ancient handprint was found in a limestone cave on Muna Island, Indonesia—and it’s shaking up what we thought we knew about our species, our creativity, and even how early humans saw themselves. This isn’t just about a handprint. It’s about the origins of expression, identity, and culture—stuff that still drives us today. So whether you’re a curious student, a history nerd, or a professional anthropologist, keep reading. This story connects all of us.

Table of Contents

7,800-Year-Old Cave Handprint

This 67,800-year-old hand stencil in Indonesia is more than just paint on stone. It’s a message across time. A reminder that humans have always needed to say: “I was here. I mattered.” And that impulse—to create, to express, to connect—is what makes us human. Whether you’re looking at ancient caves or Instagram selfies, the need is the same. To be seen. To be remembered. To belong.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

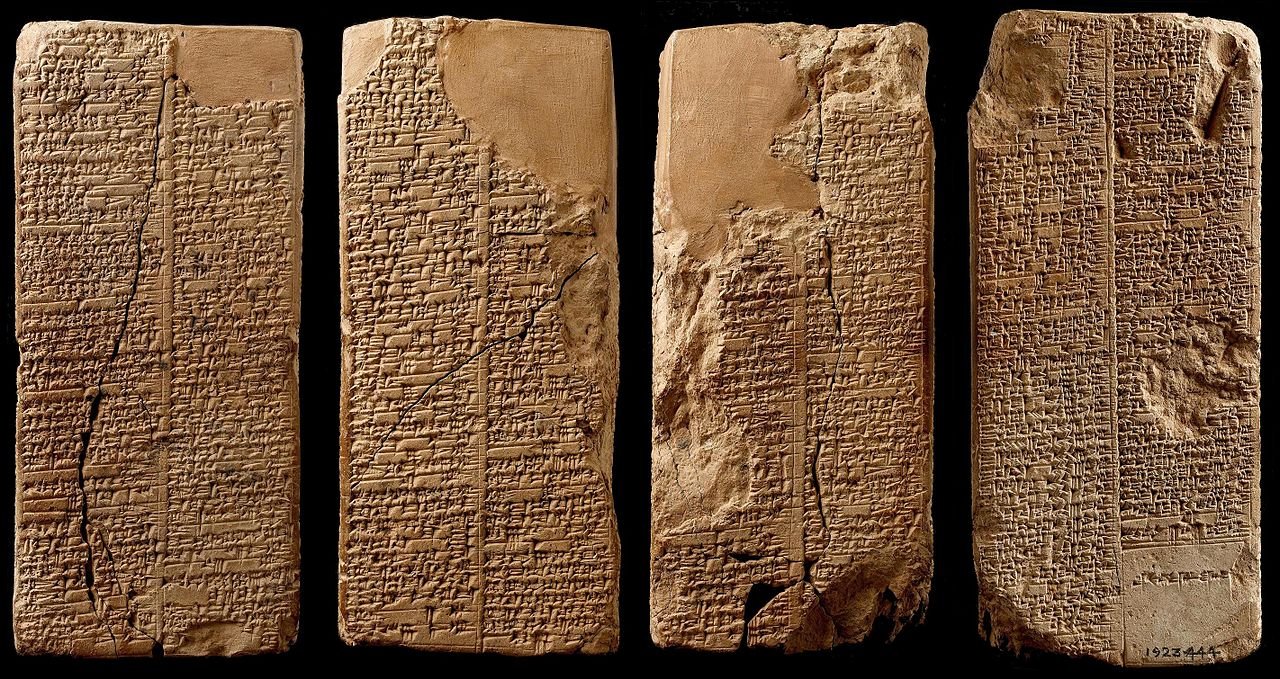

| Discovery | 67,800-year-old hand stencil found in Liang Metanduno cave, Muna Island, Indonesia |

| Significance | Earliest known symbolic human-made art |

| Dating Method | Uranium-series dating on calcite crusts above the art |

| Previously Oldest | 66,700-year-old stencil in Spain (possibly Neanderthal) |

| Maker | Likely Homo sapiens, possibly early anatomically modern humans |

| Cultural Meaning | Links to global traditions of identity, storytelling, and presence |

| Reference Source | UNESCO Indonesia |

| Published By | Smithsonian, National Geographic, Al Jazeera, PBS, Nature |

What Was Found Inside the Indonesian Cave?

In the humid depths of Liang Metanduno, researchers spotted a faint reddish outline—a left human hand, fingers splayed wide. Not painted directly, but sprayed around, leaving a “negative” image. The pigment was likely red ochre, a natural iron-rich mineral used in ancient body painting and early art worldwide.

This art wasn’t random scribbles. It was intentional. Meant to last. A message, frozen in time.

The most powerful part? The simplicity.

This wasn’t a hunting scene or religious ritual—just a human marking presence.

How Scientists Proved It’s a 67,800-Year-Old Cave Handprint?

Let’s clear something up: there was no magic trick or carbon dating of the paint. The dating method used here is called uranium-series dating—and it’s one of the most trusted techniques in archaeology.

Here’s the 5-step breakdown:

- Water in caves drips and evaporates, forming a calcite crust over everything, including art.

- Calcite contains trace uranium, which slowly decays over time into thorium.

- Scientists sampled the calcite on top of the handprint.

- By measuring uranium-thorium levels, they determined the crust was 67,800 years old.

- The handprint had to be older than that.

That’s not an estimate—that’s hard radiometric evidence.

Why Southeast Asia and Not Europe?

For decades, Europe hogged the spotlight when it came to ancient art. The Lascaux caves in France, the Altamira bulls in Spain—those were the headlines.

But over the last two decades, researchers have been quietly uncovering older and older evidence of human creativity in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia.

Past finds include:

- A 44,000-year-old hunting scene in Sulawesi, featuring human-animal hybrids

- A 51,200-year-old pig painting, also in Indonesia

- Early stone tools and symbolic artifacts in Borneo and the Philippines

This new handprint now pushes the timeline back by more than 15,000 years compared to most European finds.

Indonesia, it turns out, is a prehistoric art goldmine.

What This 67,800-Year-Old Cave Handprint Discovery Tells Us About Early Humans?

The biggest takeaway? Humans were “human” way earlier than we assumed.

By “human,” we don’t just mean physically—we mean mentally and emotionally capable of symbolic thinking. That includes:

- Understanding representation (“This image means something.”)

- Leaving messages for others

- Having a sense of identity and self-expression

This stencil isn’t just “art” in the modern sense—it’s a psychological milestone.

“This isn’t survival behavior. It’s self-expression. It’s storytelling. It’s us,”

— Dr. Maxime Aubert, archaeologist at Griffith University

Who Created This Artwork?

That’s the million-dollar question. Was it:

- Homo sapiens (early modern humans)?

- Denisovans, a mysterious hominin cousin?

- A different, lesser-known species?

Most scientists believe it was Homo sapiens, since we know they had reached Southeast Asia around 70,000 years ago, possibly even earlier. But some aren’t ruling out other human relatives.

Here’s what we know:

- Anatomically modern humans left Africa ~70,000–75,000 years ago.

- They traveled along coastal routes through the Middle East and India.

- Some groups made it to Indonesia and Australia between 65,000–70,000 years ago.

This handprint fits right into that migration window.

Bonus fact: Humans had to cross 50+ miles of open ocean to reach these islands—proof of early boating and navigation skills.

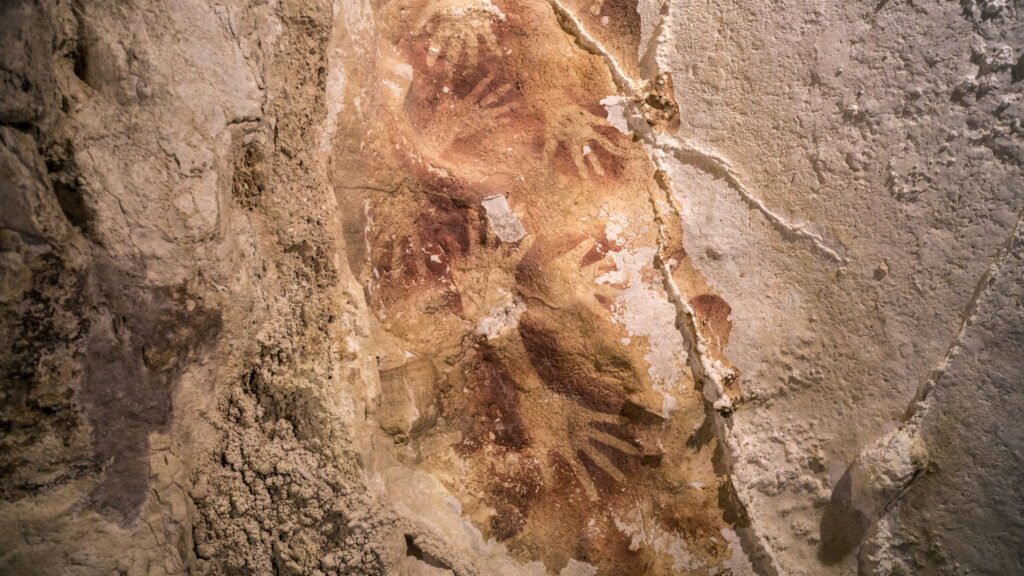

Handprints in Cultural Tradition – A Universal Symbol

If you’ve ever seen a handprint on a buffalo hide, a sandstone cliff, or a child’s school art project—you know: hands are powerful.

In Native American cultures:

- Handprints symbolized accomplishment, presence, or protection.

- The Lakota painted handprints on horses after successful raids or hunts.

- Puebloan petroglyphs across the American Southwest feature identical hand stencils to those in Indonesia.

In Australia:

- Aboriginal hand stencils are often found in sacred Dreamtime sites.

In Europe:

- The same negative hand technique was used in Spain (El Castillo) and France (Gargas) over 40,000 years ago.

No matter where you go, humans used their hands to say, “I was here.”

What Makes 67,800-Year-Old Cave Handprint a Game-Changer for Science?

This discovery:

- Extends symbolic behavior back by over 10,000 years

- Challenges Europe-centric models of human cultural evolution

- Suggests art and symbolic thought emerged independently in multiple parts of the world

- Supports the idea of a “cognitive revolution” that didn’t happen all at once, but in waves across continents

It also blurs the line between Homo sapiens and other hominins. Maybe we weren’t so unique after all—or maybe others were more advanced than we knew.

What Professionals and Educators Can Do With This?

For Archaeologists & Historians:

- Use this as a launchpad for deeper study into symbolic thought across early human species.

- Incorporate more focus on Southeast Asian archaeological sites.

For Teachers & Homeschoolers:

- Recreate a hand stencil project with natural pigments.

- Discuss how art connects us across time and cultures.

- Compare cave art globally (Spain, Indonesia, Australia, Southwest USA)

For Travelers and Conservationists:

- Encourage respectful tourism to Indonesian heritage sites.

- Support global heritage protections through UNESCO or local initiatives.

The Science and Politics of Preservation

As exciting as this discovery is, there’s a fragile side to the story.

Many Southeast Asian caves are threatened by:

- Illegal mining

- Tourism damage

- Climate change (humidity, erosion)

- Vandalism

Researchers are pushing for:

- Legal protection of all archaeological cave sites

- Sustainable access models (think: digital scanning, virtual reality)

- More funding for local conservation

Because once it’s gone, it’s gone forever.

“This handprint survived 67,800 years. Let’s not be the generation that lets it vanish,” — Dr. Adam Brumm

Did Ancient Egypt Use Disease as a Weapon Against the Assyrians?

A Handprint Made Nearly 68,000 Years Ago May Be the Oldest Human Art Ever Found

Archaeologists Identify the Oldest Poisoned Arrows Ever Found, Dated 60,000 Years