China’s Space Program Faces Trouble: China’s space program, one of the fastest-rising in the world, recently experienced a dramatic twist when three astronauts aboard the Tiangong space station were forced to delay their return to Earth. The reason? A suspected collision risk caused by orbital debris potentially damaging their return vehicle — the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft. This unexpected turn of events didn’t just ground the astronauts for nine extra days; it spotlighted one of the biggest threats in modern spaceflight: space debris. For professionals in aerospace, policymakers, and curious readers alike, this incident serves as a clear warning. It’s time to treat orbital junk as a serious global safety issue.

Table of Contents

China’s Space Program Faces Trouble

The Shenzhou-20 delay is more than just a footnote in China’s space history — it’s a stark reminder that space, once vast and untouched, is becoming a crowded and dangerous place. As China continues to expand its space station, and the U.S., Russia, India, and private companies launch more satellites, the question isn’t if debris will become a problem. It already is. We now face a fork in the road: clean up space or risk being shut out of it. The next generation of astronauts, engineers, and space tourists will thank us for the choice we make today.

| Section | Details |

|---|---|

| Event | Astronauts stranded aboard Tiangong space station due to suspected spacecraft damage |

| Affected Craft | Shenzhou-20 experienced micro-cracks potentially caused by space debris |

| Planned Return | November 5, 2025 |

| Actual Return | November 14, 2025, via Shenzhou-21 |

| Program Impact | Temporary loss of emergency escape option for Tiangong crew |

| Risk Factor | Rapidly growing low-Earth orbit debris field |

| Tracking Data | Over 100 million untracked particles in orbit |

| Official Source | China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) |

What Happened: Breaking Down the China’s Space Program Faces Trouble Incident

China’s Shenzhou-20 capsule was docked and ready to bring the astronauts home after a successful stay aboard the Tiangong space station, China’s multi-module orbital outpost.

However, during pre-return inspections, engineers noticed structural damage on the spacecraft — fine cracks that were not part of the original design. The likely cause: impact from untracked space debris. Though small, even millimeter-sized fragments can cause catastrophic damage when traveling at hypersonic speeds in orbit.

As a precaution, China’s space agency postponed the re-entry mission, opting to wait for the arrival of Shenzhou-21, which then successfully returned the astronauts on November 14.

This marked the first time China has had to delay a crewed return due to suspected debris damage — and it’s a sign of things to come unless urgent changes are made.

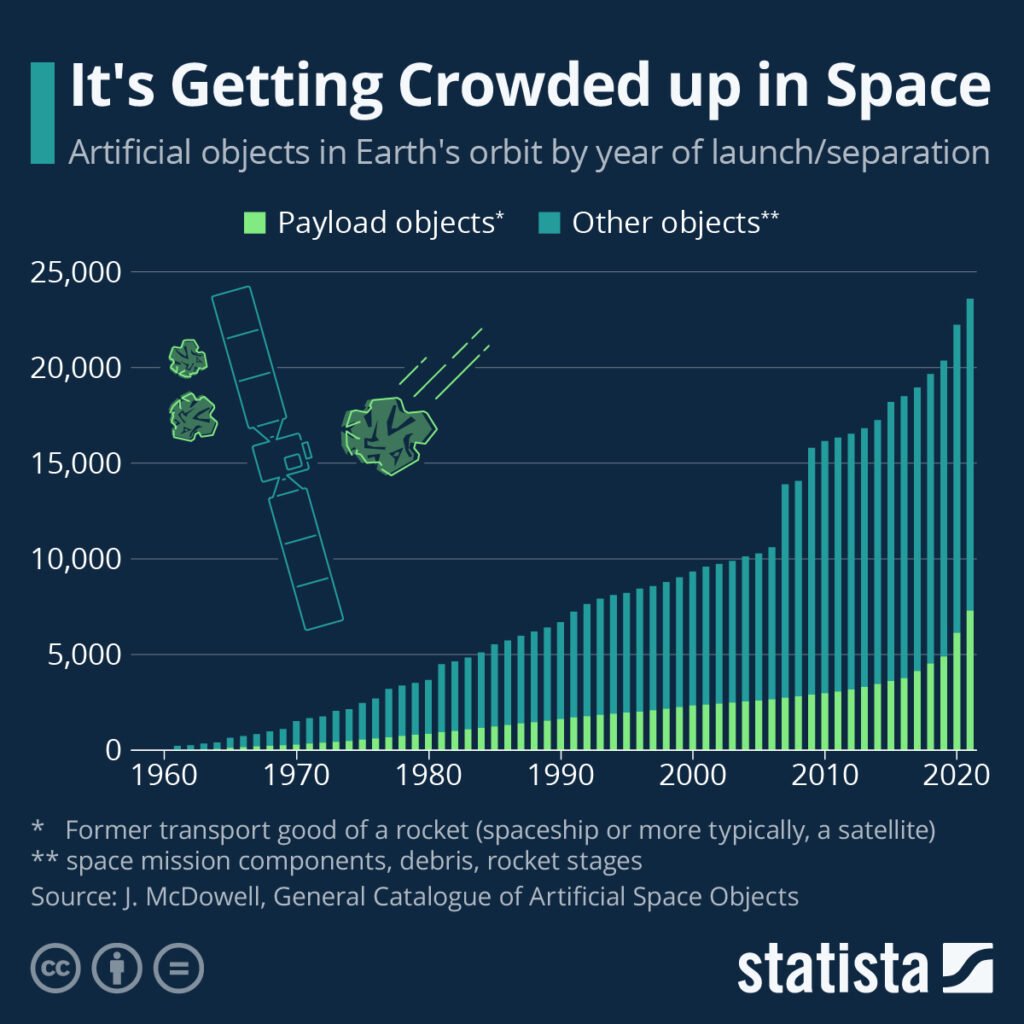

Why Space Debris is a Growing Crisis?

To understand why this event is so serious, let’s look at the bigger picture.

Space debris, also known as “orbital debris” or “space junk,” refers to defunct satellites, rocket bodies, fragments from past collisions, and even tiny particles like paint chips or bolts — all of which orbit Earth at extremely high speeds.

Current Space Debris Statistics

- 27,000+ objects larger than a softball are tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network

- 100 million+ debris particles are too small to track but large enough to damage spacecraft

- Orbiting at 17,500 mph (28,000 km/h), even a flake of paint has the force of a bullet

- More than 60 nations have launched space objects contributing to this orbital pollution

- Collisions are increasing in frequency, especially in low-Earth orbit (LEO), 160–2,000 km above Earth

How China’s Space Program Faces Trouble?

China has poured billions into its space program in recent decades, establishing itself as the third nation to independently send humans into space, and launching its modular Tiangong station to replace the now-defunct Mir and rival the International Space Station (ISS).

However, the Shenzhou-20 incident exposed some vulnerabilities:

Lack of Redundancy

When Shenzhou-20 was deemed unsafe, there was no second “lifeboat” docked at Tiangong. That’s a critical safety flaw. The U.S.-led ISS always maintains a minimum return vehicle docked, often a SpaceX Crew Dragon or Soyuz capsule, ready for emergency egress.

Had an emergency occurred aboard Tiangong during those nine days, the astronauts would’ve been stranded without a viable escape — a dangerous game of chance.

Damage Control & Response Time

The quick launch and docking of Shenzhou-21 in response shows that China has impressive launch readiness, but it also underlines the need for real-time tracking and debris response protocols that rival those of NASA or ESA.

Historical Examples: This Isn’t New

China isn’t alone in grappling with orbital debris. Here are some other close calls:

2007 – China’s Own Anti-Satellite Test

Ironically, China itself contributed massively to the debris field. In 2007, it destroyed one of its old weather satellites in a kinetic anti-satellite (ASAT) missile test, creating over 3,000 debris pieces, many of which are still in orbit.

2009 – Iridium 33 vs. Kosmos 2251

An active U.S. satellite collided with a defunct Russian military satellite, creating more than 2,000 pieces of trackable debris. This was the first-ever accidental satellite collision.

2021 – Russia’s ASAT Test

Russia blew up one of its satellites, endangering the International Space Station. The crew onboard ISS had to shelter in capsules for safety during a debris pass.

How Dangerous Is This for Astronauts?

The risk to astronauts is very real. Spacecraft are designed with micrometeoroid shielding, but they’re not invincible.

A collision could result in:

- Hull breaches

- Loss of pressure

- Navigation failure

- Uncontrolled spin or orbital decay

NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, and now CMSA conduct “conjunction analysis” — calculating predicted close approaches with known debris. But if you can’t see it, you can’t dodge it.

China’s Space Program Faces Trouble: What Should Be Done?

1. Improve Global Tracking Systems

Current systems only track objects larger than ~10 cm. We need radar and optical sensors that can:

- Detect smaller fragments

- Update positions in real-time

- Share data internationally

2. Launch Active Cleanup Missions

A few efforts already exist:

- ESA’s ClearSpace-1: Will remove a defunct satellite by 2026

- Astroscale: A Japanese startup working on end-of-life satellite servicing

- NASA’s OSAM-1: A planned robotic refueling mission

But these are one-off experiments. We need scalable, repeatable systems.

3. Set International Guidelines and Treaties

The Outer Space Treaty (1967) governs space law, but it doesn’t cover debris cleanup or responsibilities.

We need:

- Binding debris mitigation laws

- Launch licensing tied to deorbit plans

- Penalties for intentional destruction of satellites

How This Affects the Future of Human Spaceflight?

If orbital congestion continues, it won’t just affect government missions. It will slow down — or stop — plans from:

- SpaceX: Starlink constellation and future Mars missions

- Blue Origin: Orbital Reef commercial station

- NASA Artemis: Lunar Gateway space station and lunar landings

- Private space tourism: Virgin Galactic, Axiom Space, and more

A Wake-Up Call for the World

The delay of the Shenzhou-20 mission is a symptom of a much bigger disease — Earth’s orbit is polluted, and the cost of inaction is growing.

In the air, we worry about smog. In space, we need to worry about shards of metal that could cripple billion-dollar equipment or kill astronauts.

Every launch today should carry not just satellites but solutions: robotic arms, cleanup payloads, deorbit thrusters, and more.

Scientists Unveil a New Battery Concept Powered by Unusual Sulfur Chemistry

NASA Is Offering $3 Million for Help Solving a Dangerous Moon Problem

What Scientists Say Would Happen If an Asteroid Struck the Moon in 2032