How Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter: When folks hear the word hibernation, they usually picture a big ol’ bear snoozing in a cave. But let’s talk about something you might not see in cartoons — how bees and wasps actually survive winter without hibernating. These tiny powerhouses have their own clever survival tactics that’ll surprise you. And nope, it’s not just curling up and sleeping for months. Understanding these behaviors isn’t just for science geeks — it matters big time for farmers, gardeners, beekeepers, and anyone who eats food, really. Let’s dive in and break it down — no fluff, just facts, stories, and real-life strategies.

Table of Contents

How Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter?

So here’s the truth: bees and wasps don’t hibernate like storybook animals. They hustle, they prep, and they outsmart winter with nature’s best survival tools. Whether clustering together like a buzzing ball of heat or waiting out the cold alone underground, these creatures are masters of the seasons. Understanding their winter habits helps protect pollinators, support food systems, and keep ecosystems buzzing come spring.

| Topic | Key Facts & Stats | Professional Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Survival Strategies | Honey bees form heat clusters; wasp queens overwinter solo | These behaviors are diapause or overwintering, not hibernation |

| Winter Cluster Temp | Bee cluster temps can reach 90°F (32°C) in cold weather | Shivering flight muscles create heat without flying |

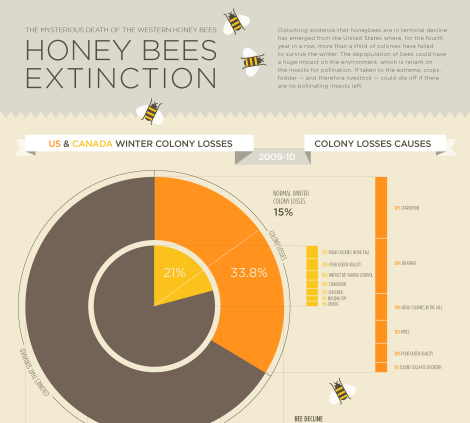

| Colony Loss Data | Over 48% of U.S. honey bee colonies lost in 2022–2023 | Winter survival is key to beekeeping and agriculture |

| Bumblebee Queens | Hibernate underground until early spring | Only queens survive; rest of colony dies |

| Wasp Queens | Enter deep diapause alone in natural or human-made shelters | Wasps don’t reuse nests, unlike bees |

| Reference | USDA Bee Health Report | USDA Bee Health |

Why Don’t Bees and Wasps Hibernate Like Bears?

Let’s clear this up first: hibernation is a complex physiological state seen in many mammals, like bears or groundhogs. It involves:

- A massive drop in body temperature

- Slowed breathing and heartbeat

- Almost no movement for months

Insects don’t hibernate this way. Instead, they either:

- Enter diapause (a suspended animation mode)

- Use overwintering behaviors like heat clustering, burrowing, or cocooning

So next time you think all bugs just “go to sleep” in winter — you’ll know better.

Honey Bees: Nature’s Winter Engineers

What’s a Winter Cluster?

If you peek inside a honey bee hive in January in Michigan or upstate New York, here’s what you’ll see: a tight, shivering ball of bees. That’s the winter cluster, and it’s how honey bees survive the cold.

Here’s how it works:

- Thousands of worker bees form a tight sphere around the queen.

- The outer bees act like insulation, while the inner bees generate heat by vibrating their flight muscles.

- As bees on the outside get cold, they rotate inward to warm up. Think of it like a slow-moving group hug.

- Cluster temperatures can rise to 90–95°F at the core — even if it’s 0°F outside.

Energy Source: Stored Honey

To maintain this heat, bees need fuel. That fuel is honey — which they’ve been packing away since spring.

- A healthy colony needs 60–90 lbs of honey to survive an average northern U.S. winter.

- Without enough honey, they starve, even if the hive is otherwise strong.

According to the Bee Informed Partnership, the 2022–2023 winter loss for managed honey bee colonies was 48.2% — among the highest in recent years.

The Queen’s Role in Winter

- The queen bee stops laying eggs in late fall.

- She stays in the center of the cluster — kept warm and protected.

- Egg laying resumes in late winter as soon as the colony senses a shift in daylight and temperatures.

That’s evolutionary genius at work.

Solitary Bees: Underground and Undercover

Over 70% of bee species in North America are solitary — meaning they don’t live in hives.

How They Do It?

- Solitary bees like mason bees, leafcutter bees, and miner bees build small nests in wood, stems, or underground tunnels.

- By late summer or fall, the female lays eggs, and the larvae spin cocoons.

- These cocoons stay dormant all winter, protected inside their nests.

They survive because:

- They enter diapause — a state of slowed development and reduced metabolic activity.

- Their enclosed homes provide just enough insulation to prevent freezing.

Note: These bees are crucial for pollinating early spring plants — even before honey bees become active.

Bumblebees: The Queen Lives On

Bumblebees (genus Bombus) live in small colonies of 50–500 bees. But when winter hits:

- The whole colony dies except the newly mated queen.

- She finds a soft, undisturbed patch of soil — often under leaves or in abandoned rodent holes.

- She digs in about 6–8 inches and hibernates for 6–8 months.

In spring, she emerges, feeds, and begins a new colony from scratch.

A study by the University of Guelph found that early spring disturbances, like landscaping or pesticide exposure, can wipe out over 70% of overwintering queens in some urban areas.

Wasps: Tough Break, But Queens Survive

Most wasps — including paper wasps, hornets, and yellowjackets — have short-lived colonies.

Fall: The Death of the Hive

- By late fall, worker wasps die off due to cold and lack of food.

- Males (drones) also die after mating.

Only the Queen Lives

- Fertilized queens search for dry, hidden spots: under bark, attic corners, behind shutters.

- They enter diapause, slowing their metabolism and using fat stores for energy.

- They don’t eat during winter and can die from dehydration or freezing if not well sheltered.

Come spring, the queen builds a brand-new nest — usually not in the same place.

Bees and Wasps Indoors: How Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter?

Ever found a wasp crawling in your attic in February? Or a sleepy bee on your windowsill in January?

That happens because:

- Warm indoor temperatures confuse overwintering insects.

- Wasps or queen bees hiding in attics may wake early, thinking it’s spring.

If they can’t get out or find food, they’ll usually die indoors. This is common in Southern U.S. homes, where mild winters don’t offer a consistent cold signal for full dormancy.

How Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter: Winter Matters More Than You Think

Understanding how bees and wasps survive the winter isn’t just trivia — it has major impacts:

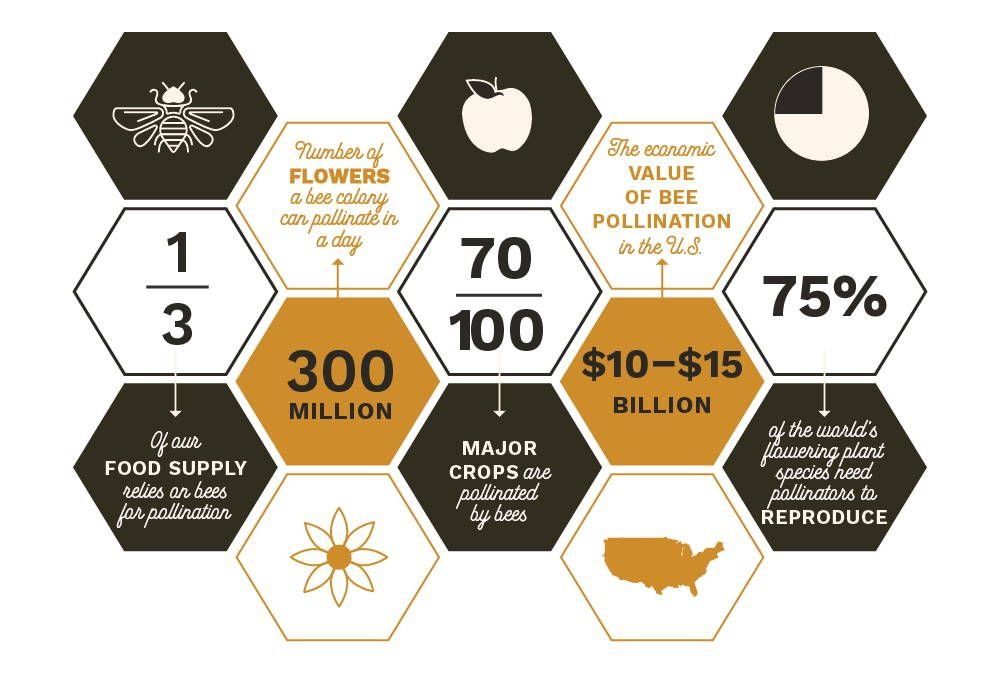

1. Crop Yields and Food Supply

Bees pollinate over $15 billion worth of crops annually in the U.S.

If winter wipes out colonies, spring pollination crashes.

2. Pest Control

Many solitary wasps are natural predators of caterpillars and garden pests. Their survival ensures a natural, pesticide-free control system for spring gardens.

3. Beekeeping Economics

A beekeeper losing 50% of colonies might spend $150–$300 per hive to replace bees in spring. That cost adds up fast for commercial operations.

Tips to Help Bees and Wasps Actually Survive Winter

Here’s what you can do — whether you manage a backyard hive or just love your garden.

Beekeepers:

- Ensure colonies are queenright and disease-free by fall.

- Feed supplemental syrup or fondant when honey is low.

- Use insulated hive wraps and moisture-absorbing boards.

- Tilt hives slightly forward to let condensation drain.

Gardeners:

- Leave stems and brush piles intact through winter — they house solitary bees.

- Avoid heavy tilling in early spring — overwintering bees may still be in the soil.

- Skip early pesticide use — it kills emerging queens and workers.

Homeowners:

- Don’t panic if you see a sleepy wasp indoors — gently remove and release outside if weather allows.

- Seal attic entry points in late summer to prevent wasp queens from nesting.

How Ancient Greek Myths Explained Where Humans Came From

The Legend of the Cursed Amethyst and the Misfortune Linked to It

Researchers Decode the Fragrances Used in Ancient Egyptian Mummy Balms