Researchers have reconstructed the Woolly Rhino Genome using preserved tissue discovered inside the stomach of a 14,400-year-old wolf pup found in Siberian permafrost. The finding, reported in a peer-reviewed study, offers new evidence about how one of the Ice Age’s most iconic mammals disappeared and suggests extinction may have occurred rapidly rather than gradually.

Table of Contents

Scientists Recover a Woolly Rhino Genome

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Specimen age | About 14,400 years old |

| Species identified | Coelodonta antiquitatis (woolly rhinoceros) |

| Major conclusion | No strong genetic decline before extinction |

Researchers say additional analysis of preserved remains could reveal how other Ice-Age animals vanished. The study underscores that extinction can occur quickly when ecosystems shift. Scientists note the discovery is not only a reconstruction of the past but also a warning about how modern species may respond to rapid environmental change.

How the Woolly Rhino Genome Was Recovered

The discovery began with the examination of a mummified wolf cub uncovered in northeastern Siberia’s permafrost region, an area known for exceptionally preserved Ice-Age remains. Scientists conducting a necropsy identified undigested muscle tissue inside the animal’s abdomen.

Because the cub likely died soon after feeding, the tissue had not decomposed significantly. Cold conditions effectively froze the material, protecting DNA fragments for thousands of years.

According to the research team, sequencing techniques extracted and assembled genetic material from the sample. This allowed scientists to reconstruct the complete Woolly Rhino Genome, marking the first time a full extinct mammal genome has been assembled from a predator’s stomach contents.

Dr. Love Dalén, an evolutionary geneticist involved in the study, said the preservation was unusual. “Normally, stomach acids destroy DNA quickly. In this case, freezing occurred fast enough that the tissue remained intact,” he explained in a university statement.

Why stomach contents mattered

Soft tissue is rarely preserved in the fossil record. Most ancient DNA studies rely on bones or teeth, where mineral structure shields DNA fragments.

Here, researchers effectively obtained fresh biological tissue compared with typical fossils. That provided longer DNA fragments and higher sequencing accuracy.

The wolf pup therefore served as an accidental biological container — preserving genetic information better than many skeletons found in soil or sediment.

The Animal Behind the DNA

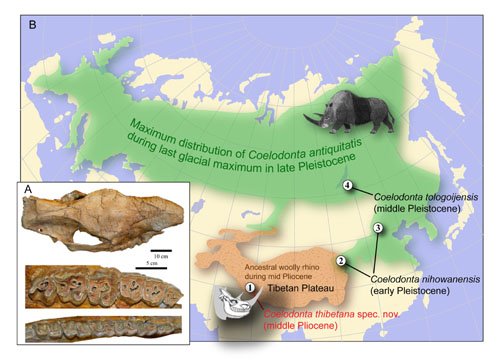

The woolly rhinoceros was one of the dominant herbivores of the late Pleistocene epoch. Roughly the size of a modern white rhinoceros, it was adapted to cold climates with thick fur, a stocky body, and a large flattened horn used to sweep away snow while grazing.

Fossils show the animal roamed from Western Europe to eastern Siberia. It lived in the mammoth steppe — a vast, dry grassland ecosystem that supported mammoths, bison, horses, and cave lions.

Unlike today’s rhinos, which live in warmer climates, the species depended on cold, open landscapes. It grazed primarily on grasses and hardy steppe plants.

Scientists say this ecological specialization ultimately made the animal vulnerable when the Ice Age ended.

What the Genome Reveals About Extinction

The woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) disappeared roughly 14,000 years ago, near the end of the last Ice Age.

Scientists long debated whether the species slowly declined over thousands of years or vanished rapidly.

The newly sequenced Woolly Rhino Genome shows relatively high genetic diversity shortly before extinction. That means populations were not suffering from severe inbreeding — a typical sign of gradual collapse.

Researchers instead found a stable population that disappeared within a relatively short time.

Dr. Dalén said the findings suggest a sudden environmental shift. “The data indicate the species was still viable. The habitat, not the genetics, changed faster than the animal could adapt.”

Climate transformation

Around that time, Earth entered a period of rapid warming. Glaciers retreated and precipitation increased. Open grasslands transformed into shrubland and wetlands.

This change reduced grazing habitat and altered food availability. Large grazers such as the woolly rhinoceros depended on dry steppe vegetation, which declined quickly.

Scientists now believe the extinction likely occurred within a few centuries — a short span in evolutionary terms.

Human Hunting — A Secondary Factor?

Researchers do not completely rule out human involvement. Humans had spread widely across Eurasia by the end of the Ice Age.

Archaeological sites show people hunted mammoths, bison, and other megafauna. However, evidence for systematic hunting of woolly rhinos is limited.

The genome evidence weakens the argument that human pressure alone caused extinction. Instead, scientists believe hunting may have compounded stress on already shrinking habitat.

The combined effect of climate change and human expansion may have pushed the species past a survival threshold.

Why This Matters Beyond One Species

The research extends beyond paleontology. It provides a new method for studying extinct animals through environmental DNA, sometimes called ancient DNA analysis in genetic research. Instead of relying solely on bones, scientists can analyze preserved biological traces left in other organisms.

The technique could help reconstruct ancient ecosystems and predator-prey relationships in evolutionary studies. It may also inform conservation science by showing how quickly climate shifts can affect healthy populations.

Researchers say the work demonstrates that extinction does not always result from gradual genetic weakening. Rapid environmental disruption can eliminate even stable species.

Implications for Modern Wildlife

Scientists studying modern conservation see parallels today. Several large mammals — including polar bears and some Arctic caribou populations — face rapid habitat changes caused by warming climates.

The Woolly Rhino Genome offers a case study of a species that remained genetically robust but lost the environment it needed.

Ecologists note that conservation strategies often focus on maintaining genetic diversity. However, the new findings show that protecting habitat may be even more critical.

In other words, a healthy gene pool cannot save a species if its ecosystem disappears.

A Rare Ice-Age Snapshot

The wolf cub itself likely died in a den collapse caused by a landslide. The frozen burial sealed both predator and prey in time.

Scientists believe the rhino tissue represents one of the youngest confirmed individuals from the species. That makes the genome particularly valuable for understanding final population conditions.

The specimen provides rare insight into everyday life in the Ice Age — including predator feeding behavior and prey availability.

Could the Species Be Brought Back?

The sequencing naturally raises questions about de-extinction.

Some biotechnology companies and research groups are exploring the possibility of reviving extinct species using genetic engineering and closely related animals.

However, scientists involved in the study stress that resurrecting a woolly rhinoceros is unlikely. There is no modern species closely related enough to serve as a surrogate.

Even if recreation were technically possible, experts say habitat conditions no longer exist.

The steppe ecosystem that supported the animal vanished thousands of years ago.

Scientific and Public Implications

The genome provides an exceptionally detailed biological blueprint of the animal. Researchers can now study physiology, adaptations to cold, immune traits, and evolutionary relationships with modern rhinoceroses.

More importantly, the discovery highlights the speed at which environmental change can drive extinction.

A paleogenomics researcher not involved in the project said the lesson is contemporary. Healthy populations can collapse rapidly when ecosystems shift beyond tolerance limits.

FAQs About Scientists Recover a Woolly Rhino Genome

What is the Woolly Rhino Genome?

It is the complete genetic code of the extinct woolly rhinoceros species that lived across Eurasia during the Ice Age.

Why was finding DNA in a wolf important?

The wolf’s frozen stomach preserved soft tissue, which usually decays quickly. That allowed scientists to recover high-quality genetic material.

Did humans cause the extinction?

Current evidence suggests climate-driven habitat changes were likely the primary factor, though human hunting may have contributed locally.

Why is this discovery scientifically important?

It introduces a new way to study extinct animals using preserved biological material rather than traditional fossils.