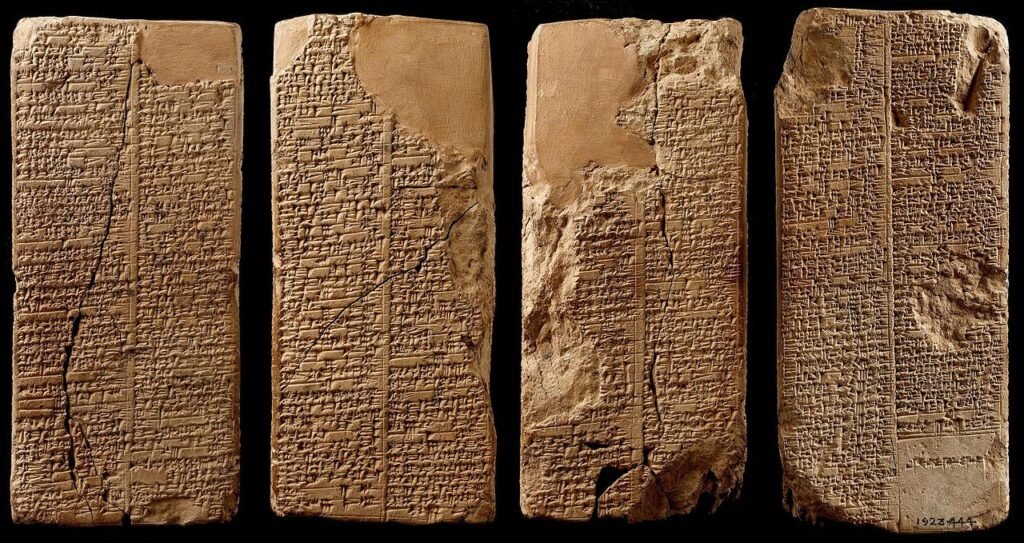

The Sumerian King List, an ancient Mesopotamian text compiled around 1800 BCE, claims that the earliest rulers on Earth reigned for tens of thousands of years before a catastrophic flood reshaped history. Preserved on clay tablets and prisms, the document blends mythology, dynastic propaganda, and early historical memory. Today, scholars view it as one of the most revealing records of how early civilizations understood kingship, time, and divine authority.

Table of Contents

Sumerian King List

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Oldest Complete Copy | Weld-Blundell Prism, dated c. 1800 BCE |

| Pre-Flood Kings | Eight rulers said to reign for 241,200 years combined |

| First Historically Verified King | Enmebaragesi of Kish |

| Purpose of Text | Political and religious legitimation of dynasties |

The Sumerian King List remains one of the most remarkable documents from the ancient world. While its earliest claims defy modern chronology, its later sections intersect with verifiable history. For scholars, it offers a rare window into how early civilizations conceptualized time, authority, and divine order. Research continues, but the text’s central message endures: kingship, in Sumerian thought, was not merely political. It was cosmic.

What Is the Sumerian King List?

The Sumerian King List is written in cuneiform, one of the earliest known writing systems, developed in southern Mesopotamia in the late fourth millennium BCE.

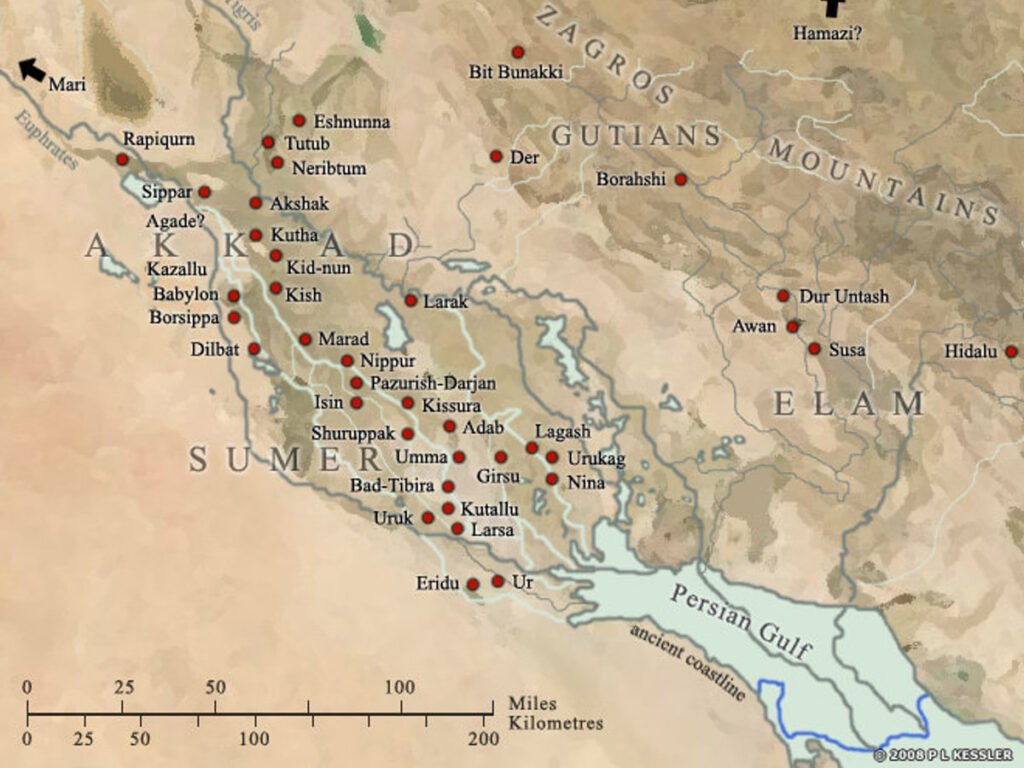

The text begins with a striking declaration: “After kingship descended from heaven, kingship was in Eridu.” From that point, it lists a succession of rulers and the cities from which they governed, including Eridu, Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Isin.

According to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which houses the Weld-Blundell Prism, the list was likely compiled during the Isin dynasty. Its structure suggests it was intended to present a single, divinely sanctioned line of kingship, even though multiple city-states often ruled simultaneously.

Dr. Marc Van De Mieroop, a historian of the ancient Near East at Columbia University, has written that the list “presents an idealized sequence of kingship, not a straightforward historical chronicle.” Scholars widely agree that it merges mythology with political narrative.

Claims of Kings Who Ruled for Tens of Thousands of Years

The most astonishing section of the Sumerian King List concerns the antediluvian, or pre-flood, rulers.

Eight kings are said to have reigned before a great flood swept over the land. Their reign lengths range from 18,600 to 43,200 years. The first ruler, Alulim of Eridu, allegedly governed for 28,800 years. Together, the eight rulers account for 241,200 years of rule.

Historians do not interpret these figures literally. Instead, many believe the numbers reflect sacred numerology. The Sumerians used a base-60, or sexagesimal, number system, which may explain why reign lengths are multiples of 60.

Dr. Piotr Steinkeller, professor emeritus of Assyriology at Harvard University, has suggested in academic studies that these exaggerated figures symbolize cosmic order and divine time rather than human lifespans.

The flood described in the list parallels Mesopotamian flood traditions, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the survivor Utnapishtim recounts a divine deluge sent to destroy humanity. Some researchers note similarities with later flood narratives in the Hebrew Bible, though scholars caution against assuming direct borrowing without evidence.

The Flood as a Turning Point

The flood marks a dramatic divide within the text. After it occurs, the list states that “kingship was lowered from heaven a second time.”

Reign lengths immediately decrease from tens of thousands of years to hundreds, and eventually to decades. This transition signals what many scholars interpret as a shift from mythic time to historical memory.

The concept of a flood resetting civilization is common in ancient Near Eastern literature. Archaeological layers in parts of Mesopotamia show evidence of localized flooding, but no scientific evidence supports a single global catastrophe of the scale described in myth.

Historians emphasize that the flood narrative served symbolic and theological purposes, reinforcing the idea that kingship was divinely granted and could be restored after destruction.

Where Archaeology Supports the Text

While early portions are widely viewed as mythological, later sections of the Sumerian King List intersect with archaeology.

One notable figure is Enmebaragesi of Kish. Archaeologists have discovered inscriptions bearing his name, making him the earliest king on the list confirmed by independent evidence. His reign is generally dated to around 2600 BCE.

Another figure, Gilgamesh of Uruk, appears in both the King List and epic literature. The list assigns him a reign of 126 years. Most scholars believe a historical ruler named Gilgamesh likely existed, though legendary elements were added over time.

Dr. Harriet Crawford, an archaeologist specializing in Mesopotamia, has noted in published research that the list becomes increasingly reliable as it approaches periods better documented by inscriptions and administrative tablets.

Political Purpose and Dynastic Legitimacy

Scholars widely agree that the Sumerian King List functioned as a political tool.

Its structure presents kingship as residing in only one city at a time, even though historical evidence shows overlapping rulers. This narrative supports the idea of a single legitimate authority sanctioned by the gods.

According to research from the University of Oxford’s Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, the list may have been composed to legitimize the Isin dynasty after political upheaval.

By placing contemporary rulers within a lineage stretching back to divine origins, the text reinforced political stability and religious authority.

Dr. Steinkeller has described the list as “a carefully constructed ideological document,” designed to unify fragmented political traditions under a coherent story of kingship.

Variations and Multiple Copies

More than a dozen fragments and versions of the King List have been discovered across Mesopotamia. These copies contain variations in names and reign lengths.

The differences indicate that scribes adapted the text over time to reflect shifting political realities. Some versions emphasize certain cities more heavily than others.

This flexibility suggests the list was not a fixed historical record but an evolving narrative aligned with contemporary power structures.

Broader Significance in World History

The Sumerian King List holds importance beyond Mesopotamian studies.

It represents one of humanity’s earliest attempts to systematize political history. The blending of myth and chronicle reflects how early societies understood legitimacy.

The document also provides insight into the development of historical consciousness. Rather than viewing history as a collection of events, the Sumerians framed it as a divine sequence governed by cosmic order.

Modern historians view the list as an early example of statecraft through storytelling. It illustrates how narratives shape political identity, a practice that continues in various forms today.

Why It Continues to Fascinate Scholars

The enduring fascination with the Sumerian King List stems from its dual nature. It is neither pure myth nor straightforward history.

Instead, it reveals how one of the world’s earliest civilizations attempted to reconcile memory, belief, and political authority.

Dr. Van De Mieroop has argued that the text teaches modern readers more about ancient perspectives on legitimacy than about exact chronology. Its value lies not in confirming reign lengths, but in illustrating how Sumerians understood power as sacred and continuous.

FAQ

Did humans really rule for 28,000 years?

No archaeological evidence supports such lifespans. Scholars interpret these figures symbolically.

Was there a real flood?

Archaeological evidence shows regional flooding in Mesopotamia, but not a single global event as described in myth.

Why was the list written?

Most experts believe it served political and religious purposes, reinforcing dynastic legitimacy.